Written by: Ali Hickerson

Free school breakfasts, in one form or another, have been a mainstay of American education for nearly a century. Increasingly, schools and state administrations are developing new ways to meet the needs of children who suffer from food insecurity across the United States.

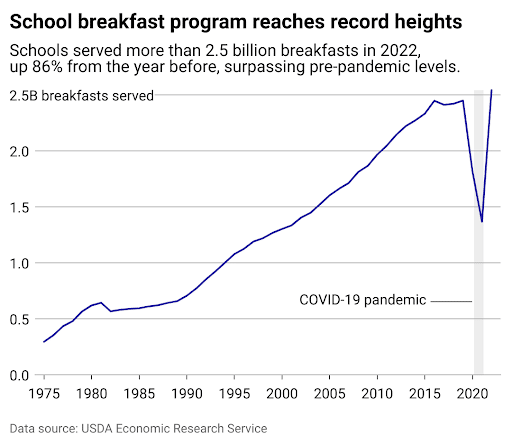

The longstanding National School Breakfast Program is a federally funded program that operates in public and nonprofit private schools, and its impact goes far beyond the cafeteria. In 2022, around 2.2 billion breakfasts were served, and the vast majority (97%) were for students on free and reduced-price meal plans.

Children are eligible for school breakfasts and lunches if they live in households with incomes at or below 130% of the federal poverty level. Reduced-priced meals are served to children from households earning between 130% and 185% of the poverty level.

Since the country first piloted the program in 1966, it has helped children in need by strengthening their health and academic potential. However, like most large-scale federal initiatives, the School Breakfast Program has faced challenges threatening its reach or scope to provide meals to kids who need them most.

Link2Feed used data from the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service to explore the history and scale of the school breakfast program.

The origins of the School Breakfast Program: From farmland to city centers

Before the School Breakfast Program was the National School Lunch Program, which sprung from a surplus of agriculture that pushed food prices down during the Great Depression. The program became permanent in 1946 when the armed forces turned away would-be World War II soldiers because they were undernourished as children.

Twenty years later, Kentucky congressman Carl Perkins championed the Child Nutrition Act of 1966, which spurred the pilot of the School Breakfast Program. His original intent was to service rural children who worked in the fields with their parents before they had a long trek to school, arriving famished. It served 80,000 children in its first year and gained traction as the Senate and media brought child hunger in the U.S. to public attention. In 1968, the pilot became a federal program, administered by states with local agreements, with food coming entirely from the United States Department of Agriculture.

However, the program didn’t meet the needs of all Americans. Around the same time, the Black Panther Party’s “survival programs” were developed, starting in Oakland, California, in 1969. The Panthers’ Free Breakfast for Children program filled crucial gaps in the federal program that failed to meet the needs of the Black community, particularly in cities. Despite its value, the FBI’s hostilities against the party precipitated efforts to foil the breakfast program. Federal agents went door-to-door, spreading misinformation that the meals were tainted, and police regularly raided locations and destroyed the food while breakfast was in service.

Women’s groups also effectively campaigned for more permanent federal change. They organized the Committee on School Lunch Participation and testified to Congress in a striking report about children in poverty left out of the school lunch program. By 1975, the federal program was made permanent, with the government providing a grant or reimbursement for each meal served that met nutrition standards.

The program grew bit by bit, and more children reaped the benefits. However, spreading the word of the new law was slow and incremental, and lack of funding or restrictions were ongoing barriers to entry. Participation finally picked up when the program moved to a performance funding model, and some states and local areas mandated high-need districts for the program. By 1990, about 44% of schools already offering free lunches also offered the free breakfast program.

Nearly three decades would pass before another program expansion when former First Lady Michelle Obama put food and nutrition at the center of her platform. Obama championed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act in 2010, which updated nutrition standards for the first time in 15 years and increased funding for the school breakfast and lunch programs for the first time in 30 years. The act also enabled the Community Eligibility Provision, which offered free meals to all students regardless of their family income as long as 40% of a school or district’s students met the criteria for low-income households. By 2016, 92% of schools offering lunch also offered breakfast; during the 2022-23 school year, 14.3 million children received breakfast.

Despite progress, the program still has room for growth. Participation in the School Breakfast Program is uneven due to local operational decisions. New York City schools, for example, offer more food daily than anywhere else nationwide, at levels comparable to the military, yet still are stretched thin after a $60 million budget cut in November 2023. In rural areas, local budgets are smaller while food costs may be higher, complicating efforts to curb the increased risk of obesity for rural children.

After the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, school meals are America’s top way to combat widespread child hunger, yet even some who are eligible reject it due to the stigma of using a program primarily for low-income families. Despite updated nutrition standards in 2010, advocacy groups contend that school lunch food is less healthy than fast food under the USDA’s oversight.

Food waste is also a concern—60% of fruits and vegetables went uneaten by students in the 2012-13 academic year due to the new requirements, according to the Special Nutrition Program Operations Study.

Breakfast program participation has grown regularly since its establishment

The program continues to innovate with unique ways to ensure kids get fed in the morning, navigating existing issues of access, affordability, stigma, and timing. Today, some schools offer grab-and-go and “breakfast after the bell” options.

While the number of breakfasts served has increased over the years, it dipped slightly around 2019 when schools were no longer required to offer the program and abruptly fell as schools closed temporarily during the initial COVID-19 outbreak. Suddenly, without two meals provided at school, a Census Bureau survey found that around 20% of children in already at-risk households reported that they sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat.

New policy initiatives helped meet needs. Many children received take-home meals and later received further financial support through the Pandemic-Electronic Benefit Transfer Program, which temporarily impacted food insecurity. Later, the Keep Kids Fed Act of 2022 kept the meal program going throughout the summer in anticipation of rising food costs.

The school lunch program continues to evolve. New guidelines that go into effect during the 2025-26 school year will cap added sugars in cereals and yogurts, and restrictions will get tighter over time. A 10% reduction in sodium in school breakfasts is on the menu for 2027-28.

Universal school meals are on the horizon. Eight states have enacted free school meals for all children, and dozens more have legislation in process. After food programs stopped after the pandemic, “Schools did not want to go back to charging some kids,” Crystal FitzSimons, director of child nutrition programs and policy at the Food Research and Action Center, told The New York Times. “They saw the huge benefits of providing free meals to all students: supporting families, supporting kids, changing the culture of the cafeteria.”

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.